Forty million people die of hunger-related causes annually. That's like the death toll from 300 jumbo jets crashing each day for a year, with no survivors, and with most of the victims children. By far the greater number of those deaths occurs in countries locked into a U.S.-dominated economic system. It has hungry nations exporting crops to those of us who are already Weight Watchers, so we can have strawberries in December, and roses for Valentine's Day. Meanwhile, those who produce such luxuries watch their children waste away.

Our banking system plays a key part in all of this. As the inescapable incarnation of the "free market," it daily exacts tons of flesh from the globe's famished. It's all part of a Third World debt-payment scheme by which poor countries transfer to the developed world three times the capital they receive from the rich in "foreign aid." The inevitable consequence of this necrophillic exchange is the carnage just described.

When on behalf of their children, the poor here and there resist such harsh discipline, our leaders and compliant media call them "communists." The very articulation of this nearly magic epithet empowers our officials to adopt virtually any Third World policy, no matter how bloody. It gives license to U.S.-trained death-squads to pay dreaded midnight visits in the name of "regional stability."

Despite such conjurings, the poor do occasionally seize control of their destinies, taking steps on their own to eradicate hunger, homelessness, and nakedness. Revolutionary Nicaragua was a case in point. But inevitably independence of this sort evokes the ire of Washington's well-fed. In response, they finance contra armies to reverse social gains, and to bludgeon and starve the recalcitrant into submission. After all, no one wants to stand accused of surrendering one of "our" backyard areas to communists.

All of this notwithstanding, the Word today is that this system of ours "works." It stands victorious for all to see. However, for the world's majority, that widespread impression represents the cruelest of deceptions. It's like telling the relatives and friends surviving the victims of the jumbo jet crashes, "Don't worry. Airplane production procedures, maintenance measures, and air traffic control systems are all O.K."

Coming face-to-face with this reality - with the hunger, with the U.S. support of Nazi-style regimes throughout the world, with our government's general war against the poor, with the deception of the reigning ideology, with the publications of Third World scholars - has formed my present political consciousness.

Of course, I didn't always think this way. In fact, it would have scandalized my parents to think that I might. They were good Catholics, patriotic and working-class - Chicagoans through and through. They raised their four children to be the same. However, they also encouraged independent thinking. Above all, they expected their children to make Christian faith the primary motive force in their lives. That primacy set me thinking about becoming a missionary priest almist from the beginning. And that direction in turn helped me critically revision my world through the eyes of Third World people; it also made me sympathetic to their understanding of the Gospel.

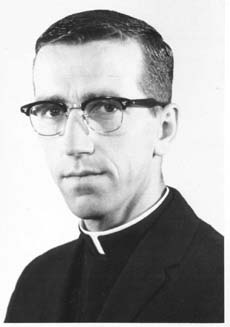

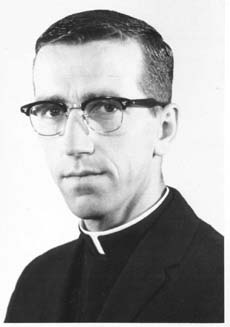

|

|---|

| My ordination picture. I was ordained on December 22nd, 1966. |

My growth in political consciousness was gradual however. Virtually up till my ordination to the Catholic priesthood in 1966, I was largely apolitical and uncritically pro-American. I cast my first vote in a national election for Barry Goldwater.

This ethnocentrism began to erode when I left the United States to pursue graduate studies in Rome. For the next five years, I lived in an international community of Irish, British, Australian, and North American clerics. I studied moral theology in the Academia Alfonsiana with students from across the globe. All in this setting were free with their criticisms of the United States, and seemed much more politically literate than I. So I took on the task of catching up - of trying to make sense of the world. I devoured news magazines weekly. I studied the history of my own country as never before.

This was the period just after the Second Vatican Council, an important time for Catholics, since it was an era when a spirit of critical thought entered the church. Priests like me were asking questions they previously would never have dreamed raising. This spirit invaded the political realm as well. If the sacrosanct Church and its hierarchy could be so thoroughly and fundamentally scrutinized in the name of the Gospel, why not the nearly as sacred State and its politicians?

In this context, my doctoral studies introduced me to "liberation theology." This strain of largely Latin American thought demonstrated how the structures of international capitalism were basically responsible for the widespread miseries of the Third World. (Later, in 1984, I was to see this for myself, while studying with some of the region's best theologians in Brazil.) Moreover, liberation theology interpreted the Bible as the expression of God's "preferential option for the poor and oppressed." Biblical scholarship, I found, supported that conclusion.

Following my decision to leave the canonical priesthood in 1974, I began teaching General Studies and Religion at Berea College in Kentucky. This gave me the chance to continue my study of liberation theology, while affording me the opportunity to teach it occasionally. Thus my political awakening entered another phase through my teaching, professional extra-curricular activities, and travel in the Third World.

Following my 1984 sabbatical in Brazil, two trips to Nicaragua, one for five weeks in 1985, and another for a month in 1989, have made extremely important contributions to my political education. They brought me into further contact with the living conditions of working-class people on the receiving end of U.S. Third World policy. The contrast between what I observed in Nicaragua and what our government said about that country was astounding. It pointed to the fundamentally dishonest character of our national leadership. In addition, I discovered books and other sources of information in Nicaragua which exposed Third World viewpoints largely unavailable in the United States. This underscored the one-sided bias of our mainstream press, scholarship, and teaching.

What's clear from all this is that my life's experience has made me terribly suspicious of our government. Revelations connected, for instance, wiht the Iran-contra scandal heightened the suspicion exponentially. I clearly recognize a long string of misleading stories, cover ups, and paper-overs foisted upon the North American public. Contragate, Vietnam, and Watergate are the rule, not the exception. Sad to say, they represent the way our government does business. Such business inevitably yields horrific dividends like the September 11th "attack on America." In the end, I've concluded that the burden of proof will always rest with our officials, rather than with our country's designated Third World enemies.

- Mike Rivage-Seul

| Copyright

© 2002, Berea College Updated 10/14/02 URL: www.berea.edu/GST/Rivage-Seul/AutobiographicalReflections.html Information prepared by Mike Rivage-Seul, mike_rivage-seul@berea.edu. Page maintained by Sandy Bolster. |